![]()

“With its allusions to, and fierce polemical discussions about,

the occult, conspiracy theories, cultural imperialism in the

shape of creeping Americanisation, mass murders, female

promiscuity, Satanic abuse, the shortcomings of

materialism, hysteria, alchemy, alternative religions,

homeopathy, mysticism and hypnotism, the novel [Là-Bas]

is a compendium of the anxieties, fears and delusions

of the late nineteenth century.”

-Brendan King, from his introduction to the 2001 Dedalus Press

English translation of J.K. Huysmans’ 1891 novel Là-Bas

Anyone even remotely familiar with the history of Western rock music has probably seen, at one point or another in their life, the cover art of Pink Floyd’s

The Dark Side of the Moon album, which is widely considered to be one of the most recognizable and iconic album covers of all-time: a single beam of light entering a prism, said beam of light then refracting as a rainbow-colored spectrum of light. I think some of the best books are like that, with the initial beam of light serving as the reader’s attention, and the prism representing a book: that is, you go into a book with the intention of reading it, but sometimes you’ll discover things in that book that will send your attention (or focus) into a variety of new and unexpected directions. With this essay I intend to talk about J.K. Huysmans’ classic 1891 novel

Là-Bas (often translated into English as either

Down There or

The Damned), which I often rank in my top-ten favorite novels ever written. But before I get into that, I would first like to briefly mention how I first came to learn about the novel, mainly to both illustrate and also to justify the verbose metaphor that I chose to begin this article with.

In the year 2004, during a time in my life in which I was a dabbler in the occult arts, I began to explore the books of Kenneth Grant, mainly his well-regarded Typhonian Trilogies, which at that time were widely out-of-print and hard to find at a low price (this was several years before Starfire Publishing began reprinting them). Having read Kenneth Grant’s

Nightside of Eden earlier that year, I eventually got my hands on a copy of

Cults of the Shadow that summer. Like

Eden, Cults of the Shadow is a very fascinating book, presenting the reader with a panoramic examination of various cults of the Vama Marg (or Left Hand Path of occultism) throughout history, beginning with ancient African, Egyptian and Eastern Tantric sects before analyzing the work of assorted 20th-century occultists, including Aleister Crowley and Austin Osman Spare (two men that Grant had in fact been both acquainted with and a student of), Frater Achad, and the Chicago-based voodoo master Michael Bertiaux (whose

Voudon Gnostic Workbook I would consider to be one of the most singularly bizarre tomes I’ve ever come across, even by the outré standards of occult texts). On the first page of the first of the two chapters that Grant devotes to Bertiaux’s so-called Black Snake Cult (or

La Couleuvre Noire, to use its French name), Grant writes the following:

“With Michael Bertiaux, the Voodoo-Gnostic Master of the

Cult of La Couleuvre Noire, we step into the heavily charged atmosphere that lingers on in the wake of the Mages of the French Decadence. The

revenants of the Decadence live on, and their present-day equivalents in downtown Chicago are stalked by the shades of Joseph Péladan, Stanislas de Guaita, Pierre Vintras, J-K. Huysmans, and the sinister original of Canon Docre - the Abbé Boullan - with whom Bertiaux claims to be in direct astral communication. Yet this atmosphere of nostalgia surrounding

The Monastery of the Seven Rays, which Bertiaux also directs, is redolent not only of the strange and diabolical rites performed by a Gaufridi, or by a Guibourg when he wove the sinister spells to which the evil fascination of Madame Montespan added its bouquet of morbid loveliness, but of a more vital and elemental power that enhances to its highest pitch the aetiolated atmosphere of the Decadence. I refer to the monstrous shadows conjured by the New England enchanter, Howard Phillips Lovecraft, for Michael Bertiaux claims to have established contact with the ‘Deep Ones’, the fearful haunters of Outer Spaces that Lovecraft has brought so close to earth in his terrifying fictions.”

In regards to a footnote to the name Canon Docre that appears on this same page (which is page 161 of the Starfire Publishing reprint), Grant writes, “He features in

Là-Bas, the novel by J-K. Huysmans based on the author’s actual experience of the darker byways of occultism. See also p. 170, note 22,

infra.”

(For the curious, note 22 on p. 170 states the following: “Another discarnate human spirit claimed by Bertiaux is the Abbé Boullan (1824-93), a French occultist whose name and activities would probably have remained unknown to the world at large but for the attention he received from J-K. Huysmans, who used Boullan as the model for ‘Dr. Johannes’ in his novel Là-Bas (q.v.) According to

The Encyclopaedia of the Unexplained (Ed. Richard Cavendish, London, 1974), ‘Boullan believed that the path to salvation lay through sexual intercourse with arch-angels and other celestial beings.’”)

It was in the above passages that my acquaintance was first made with

Là-Bas. Needless to say, at that point in my life those passages caused me to ask myself a lot of questions. What exactly was the French Decadence? Who were this Huysmans and Boullan? How did one have sex with angels? Who were Vintras, Gaufridi, and Guibourg and, for that matter, what the hell did the word ‘aetiolated’ mean (in regards to that latter question, it’s actually a British spelling of the American word ‘etiolated,’ the definition of which here is ‘…to cause to become weakened or sickly; drain of color or vigor’).

Still, at the time I first came across that passage, I was far more interested in reading about Bertiaux than I was in investigating the work of J.K. Huysmans. But it was always in the back of my mind. Fast-forward to the first week of July 2006. While doing a closing shift at the Barnes & Noble where I worked, I happened to spot, while returning another book to its proper place on the shelves, J.K. Huysmans’

Là-Bas on one of the shelves in Fiction. Remembering that passage from Kenneth Grant’s book, I took the book off the shelf and looked it over. It was the Dover Press edition (a 1972 unabridged republication based on the 1928 Keene Wallace English translation), the front cover featuring a recolored detail from an Odilon Redon lithograph (the lithograph being “Death: ‘It is I who makes you serious…,” which is No. 20 of the third series of his

La Tentation de Saint-Antoine, 1896). Impressed by the suitably macabre and Gothic-looking cover art, I flipped the book over to read the novel’s description on the back. I here reprint the novel’s description in full, not to bore you to death with petty details (though it’s probably already too late for that), but simply because I think it’s one of the greatest book descriptions I’ve ever read, and I would probably have a hard time picturing someone reading such a book description and not being obsessed with reading the book in question as soon as possible:

“This novel is the classic of Satanism. It caused a sensation when it first appeared in 1891 because of its extraordinarily detailed and vivid descriptions of the Black Mass. These descriptions are also authentic, for J.K. Huysmans, who has been called the greatest of the French decadents, had first-hand knowledge of the satanic practices, witch cults and the whole of the occult underworld thriving in late nineteenth-century Paris.

At its center is Durtal, a writer obsessed with the life of one of the blackest figures in history, Gilles de Rais. The legendary crimes, trial and confession of this enormous and grotesque fifteenth-century child murderer, sadist, necrophile and practitioner of all the black arts unfold in episode after horrifying episode. Mystical thematic threads connect this greatest of all revelers in evil with Durtal’s own passionate pursuits, the reflection of a religious quest that was to lead Huysmans from uncertain agnosticism back to Catholicism.

Durtal, the mouthpiece for the strange personality of Huysmans, leads a hermit-like existence cloistered from his fashionable contemporaries. Surrounding him are others equally cut off, sharing a nostalgic longing for the Middle Ages. There is a simply religious bell-ringer, a learned astrologer, a medical doctor versed in homeopathy and occult lore, and a fourth person- a sheltered, unsatisfied bourgeoisie by day and mysterious succubus by night. They take refuge where they can from the forces of modern times- in a bell tower, in abstruse knowledge and in diabolism.

Huysmans’ ability to mesmerize his readers with torrents of sound and image is itself suspiciously akin to the magical arts. His intoxication with the abominable and the depraved is magnified by his extreme sensitivity. He combines grimly realistic detail with esoteric knowledge, and searches relentlessly for the divine in the depths of evil and in the furthest reaches of human experience. The republication of this novel, along with the previous publication of

Against the Grain (Dover 22190-3) will make him accessible to the larger audience who will surely find him both important and fascinating, as have Oscar Wilde, Havelock Ellis, and many other major literary figures.”

I first read

Là-Bas during the summer months of 2006, and while I loved it at the time, it still hadn’t become a true obsession. That all changed in 2008, when I became very interested not only in French literature, but in particular the literature that sprung forth from the 19th-century French Decadent movement. That year I began to read such writers as Remy de Gourmont, Jean Lorrain, Rachilde, Octave Mirbeau and, most pertinent of all, J.K. Huysmans. That year I also read, for the first time, a number of Huysmans’ other novels, including

Against Nature, Downstream, En Rade, and

En Route. I also re-read

Là-Bas, and it was here that my obsession with the novel truly began. Curious to learn more about how the novel was written (as the Dover Press edition I owned had nothing in the way of an introduction or any sort of essays, footnotes or endnotes), I began to collect other editions of the book, including the Penguin Classics edition and the Dedalus Press edition (the latter having been translated by noted Huysmans scholar Brendan King). I also began collecting any other book I could find on Huysmans’ life, including Brian Banks’

The Image of Huysmans (AMS Press, 1990),

The Road From Decadence: from Brothel to Cloister: Selected Letters of J.K. Huysmans (The Athlone Press, 1989, edited by Barbara Beaumont), and, most crucial of all, Robert Baldick’s celebrated

The Life of J.K. Huysmans (which is still the definitive biography of Lovecraft’s life). Through these sources and others, I began to learn not only more about Huysmans’ life, but also how the book

Là-Bas came to be written (indeed, the events that transpired around Huysmans’ life during the course of the writing of the novel are almost as bizarre in nature as the novel itself). Here, then, is the fruit of that labor. Following a brief summary of the novel, I will then go on to discuss how it came to be written, examine its characters (and the real-life people who influenced a few of them), and analyze the novel’s reception and aftermath. Much of this information has been taken from the books just listed above (in particular the Baldick biography), but for the sake of convenience I’ve grouped all that they have to say about

Là-Bas here in one location.

Although I’ll be the first to admit that this tribute is a lengthy read, those who stick with it will encounter (I hope) a mesmerizing tale of demonic possession, Black Masses, occult warfare, astral sex, human sacrifice, conspiracy theories, secretive cults and sects, witchcraft, succubae, whores, STDS, and, ultimately, religious salvation. But first we must turn away from the everyday monotony of Modernism and, like the characters that populate

Là-Bas, immerse ourselves in the nostalgias of the past. The place is Paris, the Poisoned City, and the time is the late 1800’s, specifically the latter years of the 1880s and the early years of the 1890s: the tail end of the

fin de siècle. It is during this transitionary period, which originated with the Decadent movement and climaxed with the Catholic Revival, in which J.K. Huysmans penned the book with which we now concern ourselves.

Là-Bas is the first book in the series of four novels that has unofficially come to be classified as the Durtal tetralogy (the other books in the series are

En Route, The Cathedral, and

The Oblate of St. Benedict, in that order). Collectively, they chart the progress of a man’s soul, from the lowest depths of sin to the heights of Grace, the man in question being Durtal. The books are semi-autobiographical in that Durtal’s spiritual quest is almost virtually identical to that of Huysmans’. But it all started with

Là-Bas. Essentially,

Là-Bas is a book about a man writing a book. Such a thing is common in these times, but back in the 19th-century, this type of approach in fiction was still fairly fresh. The book takes place in Paris, France, sometime around the years 1889-1890 (the last chapter most likely is set in January of 1890, if the references to Boulanger’s victory of the election are anything to go by), and follows the exploits of Durtal, a middle-aged bachelor who is struggling to write a historical book on the life and crimes of the notorious Gilles de Rais. While researching the Satanism of the Middle Ages, he comes into contact with a strange cast of characters who reveal to him that not only does Satanism still exist in modern times, but that it is all but thriving in

fin de siècle France. Durtal comes to be seduced by a mysterious woman who is herself a Satanist, and she eventually takes him to a Black Mass, which serves as the closest thing the novel has to a climax. So the book is really two books in one: one plotline dealing with Durtal’s researches in regards to Gilles de Rais, and the other being his investigations into the Satanic groups of modern times.

As Brian Banks noted in his book

The Image of Huysmans, “The atmosphere of Paris, the novel’s setting, becomes almost Gothic, bathed in mists of sinister, almost evil, mystery. A modern Babylon, conjured up in a pungent style that has by no means dated. The historical data, excepting that upon Boullan, is true and real enough to send one into cobweb-libraries and shadow-castle ruins, in quest of the ghosts of such a rich, vibrantly alive tapestry.” To read this novel, then, is to immerse oneself into “…a twilight world of black magic and erotic devilry in

fin de siècle Paris” (to quote the back cover of the Penguin Classics edition of

Là-Bas).

If there’s one lesson I learnt from Huysmans as a writer, it is the importance of information overload (other writers I like who use this technique include Grant Morrison, Kenneth Grant, H.P. Lovecraft, and Thomas Pynchon): that is, blitzing the reader’s attention span with a seemingly unending spectrum of facts, dates, pseudohistory, documentation, scientific material, strange use of vocabulary, specialized occult jargon, and so on: in this way, the author can trick the reader’s psychic censor and slip ideas into their subconscious mind that they might not readily accept while in a more lucid frame of mind. To me

Là-Bas is so much more than a mere novel: the reader who wanders through its pages will encounter many learned discussions on everything from the crimes of Gilles de Rais, the secrets of alchemy, the symbolism of church bells, the art of astrology, how to poison someone from long distance using white mice and desecrated communion wafers, the pros and cons of Naturalism as a literary genre, why the larvae that devour obese corpses differs from those that can be found in thin cadavers, the Spermatic Mass, how to boil a leg of lamb, why the penis of the incubus is two-pronged… the list goes on and on. Eventually, the reader has no choice but to submit to Huysmans and realize that he’s simply smarter and better read than they’ll ever be. Of course, one of the main reasons to read Huysmans is to see his style in action and to be amazed at his colorful use of vocabulary (as he applies the techniques of painting in the construction of his novels). But simply put,

Là-Bas just has some very beautiful images and sentences. The following two sentences are some of my favorites in all of literature:

“Really, when I think about it, there’s only one reason for literature to exist, to save those who write it from the tedium of living!”

And:

“Art should be like the woman one loves, out of reach, in another world, distant, because in the end, along with prayer, it’s the only proper expression of the soul.”

One final thing to note before we begin: if there’s one fact I want you to keep in mind about Huysmans as you read over this essay, it’s that he was

extremely gullible, and would often believe things solely on the word of someone else, without exerting much effort to question the source.

![]()

“Satanism is based on the manipulation of energy and consciousness. These deeply sick rituals create an energy field, a vibrational frequency, which connects the consciousness of the participants to the reptilians and other consciousness of the lower fourth dimension. This is the dimensional field, also known as the lower astral to many people, which resonates to the frequency of low vibrational emotions like fear, guilt, hate and so on. When a ritual focuses these emotions, as Satanism does, a powerful connection is made with the lower fourth dimension, the reptilians. These are the ‘demons’ which these rituals have been designed to summon since this whole sad story began thousands of years ago. This is when so much possession takes place and the reptilians take over the initiate’s physical body. The leading Satanists are full-blood reptilians cloaked in human form. These rituals invariably take place on vortex points and so the terror, horror and hatred, created by them enters the global energy grid and affects the Earth’s magnetic field. Thought forms of that scale of malevolence hold down the vibrational frequency and affect human thought and emotion. Go to a place where Satanic rituals take place and feel the malevolence and fear in the atmosphere. What we call ‘atmosphere’ is the vibrational field and how it has been affected by human thought forms. Thus we talk about a happy, light or loving atmosphere, or a dark or foreboding one. The closer the Earth’s field is vibrationally to the lower fourth dimension, the more power the reptilians have over this world and its inhabitants.”

-David Icke,

The Biggest Secret

Là-Bas: The CharactersLike many of Huysmans’ novels, many of the characters that populate

Là-Bas are based on (or are composites of) real-life people that Huysmans knew or associated with. We will now look at the cast of characters of

Là-Bas. When I read books, sometimes I have a tendency to keep count of how many pages each character appears on, so I can get an idea of which characters tend to appear the most. I did the same thing with

Là-Bas upon re-reading it during the opening months of 2015, and I here rank the characters by the number of pages they appear on (using the Dedalus Press edition as the text in question).

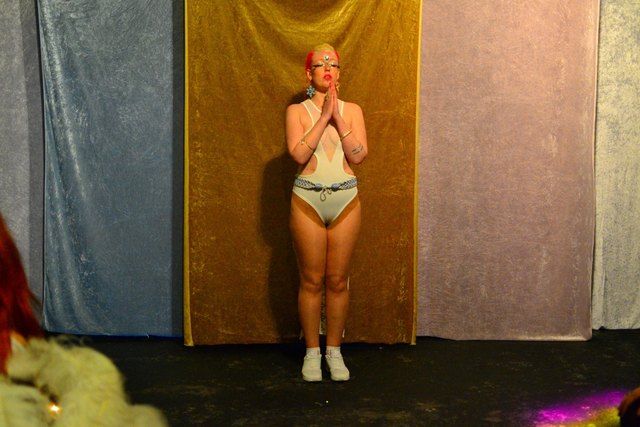

J.K. Huysmans in 1894

DURTAL: Durtal is the main protagonist of

Là-Bas, appearing in 270 of its 278 pages. Durtal, like Huysmans, is a novelist, specializing in the genre of Naturalism (though no details are given as to the names or subject matter of his previous books: it is revealed in the second chapter of

Là-Bas that is has been two years since his last book was published). At the start of

Là-Bas, Durtal has grown tired of the Naturalism genre and the Parisian literary scene in general (as Huysmans himself had become at the time), and is seeking to branch out into new literary territory. Repulsed by Modernity and inspired by the Middle Ages, he conceives of a new type of literature (“Spiritual Naturalism”), and begins work on a biography of Gilles de Rais (who he classifies as a ‘des Esseintes of the 15th century”). Durtal is a bachelor (his family had died long before the start of the novel), and he leads a lonely life in his 5th floor apartment (which costs him 800 francs a month) on the Rue du Regard in the Left Bank (the 6th arrondissement, I believe), his only company being his pet cat Mouche (a French word that means “fly,” as in the insect) and the occasional visit from his best friend des Hermies. Not much physical descriptions of Durtal are given, aside that he’s around 40 years of age, with a short figure, tired eyes, black hair, an untidy moustache, and a sad and thoughtful face. We learn that his favorite artists are the Flemish and Dutch Primitives, and that some of his preferred writers include Flaubert, the Goncourts, Zola, Dostoevsky, Balzac, Ernest Hello, Anne Emmerrich, Ruysbroeck, and Baudelaire. Although on one hand he finds himself drawn to Catholicism (and religious belief in general), at the same time his carnal appetite is quite strong, and he enjoys the occasional brothel visit every now and then.

Essentially, Durtal is an idealized version of J.K. Huysmans himself. Originally the character was to have been named Runan, though this was (obviously) eventually changed. One day, while lunching with a friend of his (Dr. Michel de Lezinier) at a restaurant in the Place Saint-Andre-des-Arts, Huysmans overheard his friend mention how his family name was that of a village that lay between Angers and La Flèche, near the town of Durtal. Huysmans instantly became fascinated with this name and ended up using it as the name for his main character (see pages 231-232 of the Dedalus edition of the Baldick biography for a more detailed explanation of this story).

1878 painting of Huysmans by Jean-Louis Forrain

DES HERMIES: a doctor of medicine and Professor of Science (though he has no faith in the accuracy of modern medicine), des Hermies is Durtal’s best friend and closest confidant, and he appears in around 115 pages of the book. He is described as fair-haired, tall, slender, and very pale, with close-set eyes of a deep blue color over a short and inquisitive nose. Or, as Huysmans writes, “He had about him the air of a sickly Norwegian and an acerbic Englishman.” Like Durtal, des Hermies also incorporates some aspects of Huysmans’ character (Huysmans could be describing himself when he writes the following about des Hermies: “He was methodical, watchful and as cold as an icicle in front of people he didn’t know; his superior and somewhat awkward attitude was matched by his hollow laughter and peremptory manner. At first sight, he could inspire a real apathy, which he would often justify by his venomous words, scornful silences and severe, mocking smiles. He was respected in the Chantelouve circle and feared still more, but when you came to know him, you discovered that beneath his frosty countenance lay a genuine kindness, an affection that, if not expansive, was capable of a certain heroism and could always be relied on”), though his main purpose in the book is mainly to serve as a sounding board to Durtal. Des Hermies is a very erudite man, “a prodigy who knew everything, who was familiar with the most ancient of old books, the most time-honoured of customs, and the most up-to-date discoveries,” a man who can always be found in the company of “astrologers and kabbalists, of demonologists and alchemists, of theologians and inventors.” He also has something of a dark side: in one scene he mentions visiting a restaurant every now and then and observing how, each time he visits it, the regulars of the place are slowly wasting away from the poisonous food being served, and how he plans to continue going there once a month to take in the spectacle of their slowly wasting away. In terms of religious belief, he doesn’t really believe in anything but leans towards the concept of Manicheanism. He lives on the Rue Madame.

LOUIS CARHAIX: the bell-ringer of the Church of Saint-Sulpice, a post he has held for 15 years. He appears on 61 of the book’s 278 pages. A close friend of des Hermies (who he has known for around ten years), he also becomes a friend of Durtal during the course of the book. Unlike Durtal and des Hermies, Carhaix is a staunch Roman Catholic. A Breton, he is described as having prominent blue eyes, a neat and Germanic moustache, and “the pallid, bloodless complexion of prisoners in the Middle Ages, a complexion now unknown, of a man imprisoned until the day of his death in a wet dungeon, in a dark, airless cell.” Born in Brittany, it was there that he attended a seminary, but upon deciding he was unworthy of being a priest Carhaix dropped out and moved to Paris, where he became a pupil of the master bell-ringer Father Cilbert at Notre-Dame, and it was there he learned the art of bell ringing, before becoming the bellringer of Saint-Sulpice. Carhaix’s primary passion in life are his bells, and he gives many lectures in the course of the book on the art and symbolism of bell ringing.

![]()

Saint-Sulpice Church, where much of the novel takes place

Carhaix’s real-life analogue is a man known only as Contesse, who was also the bell-ringer at Saint-Sulpice (having begun working there in 1878): like Carhaix, he too lived in the north tower of that church. Huysmans first met him in the winter months of 1888, and did visit him several times, but they never really became friends. Apparently this Contesse believed that the only real reason that Huysmans was visiting him was to court his daughter (“a strapping wrench of some twenty summers,” as Huysmans described her), and when he became convinced that Huysmans was merely toying with her affections, he ordered Huysmans to leave his apartment and never return. Carhaix’s lengthy discourses on the art of bells and bell-ringing are not attributed to anything said by this Contesse: Huysmans merely got the information from a book entitled

Art de la sonnerie by Lamiral.

Berthe de Courrière (bust)

HYACINTHE CHANTELOUVE: the

femme fatale of

Là-Bas, Hyacinthe Chantelouve serves as Durtal’s portal into the world of modern-day Parisian Satanism. Appearing in 49 of the novel’s pages, she is the wife of Monsieur Chantelouve (who is actually her second husband: her first husband, a maker of church vestments, committed suicide under mysterious circumstances), and lives at the Rue de Bagneaux. She is 33 years of age, a small-boned, narrow-hipped, slender (though not too thin) and delicate woman with wild blonde hair, a woman who is, while not pretty, still striking, with a big nose, passive lips, superb mouse-like teeth (yes, Huysmans actually describes her teeth as mouse-like), and enigmatic and smoky eyes that are ash-gray in color. Hyacinthe enjoys seducing both writers and priests alike, and much of the middle portion of

Là-Bas revolves around her relationship with Durtal: this relationship begins with a number of impassioned fan letters which she writes to him, until they eventually meet in person and, gradually, begin having sex with each other. Although Durtal is both intrigued and obsessed by her, his main interest in her is her friendship with Canon Docre (see below). Their relationship falls apart when she takes him to a Black Mass, and he realizes that beneath her air of sanctity she is a “truly nasty Satanic woman” (literally speaking: during the Black Mass scene she even describes Satan as her “Master”). Still, in the end, he decides that for all her diabolical quirks she’s still not as interesting as Gilles de Rais.

One of the real-life inspirations for the character of Hyacinthe was Berthe de Courrière (June 1852-June 14, 1916), an artist’s model and demimondaine of notorious reputation. Born in Lille, (a city in the north of France), she moved to Paris in 1872. Best known as the mistress of several notable French personalities of the late 19th-century, including the General Georges Boulanger and the sculptor (and son-in-law of George Sand) Auguste Clésinger (the latter of whom used her as the model for his bust of Marianne at the Sénat),

Berthe aux grands pieds (“Bigfoot Bertha”) was also the mistress of the writer Remy de Gourmont, whom she met in 1886. When Huysmans befriended de Gourmont in 1889, he would begin to visit the flat in the Rue de Varenne which de Gourmont shared with Berthe. The interior decoration of her flat was half-Pagan and half-Catholic in its aesthetic sensibilities, and whenever Huysmans visited her she would discourse at great length on her experiences in the occult arts (these visits and conversations inspired the dinner scenes in

Là-Bas, though in the novel they instead take place in the bell tower of Saint-Sulpice). One evening Huysmans even took part in a séance that was held at Berthe’s flat.

Berthe was notorious for her acts of sacrilege: she was known to seduce priests, and the writer Rachilde professed to once seeing Berthe take consecrated hosts out of her shopping bag and feeding them to stray dogs. She was also mentally unstable, and twice during the course of her life she was certified insane and committed to asylums. Oddly enough, despite her occult and satanic dabbling, she would play an instrumental role in Huysmans’ reversion to Catholicism, as will be seen below.

artistic depiction of Madame Chantelouve by Henry Chapnot,

from an edition of Là-Bas published in 1912

Another real-life woman who inspired the character of Hyacinthe was Henriette Maillat, whom once had a brief (and unhappy) love-affair with Huysmans (most likely around 1888/early 1889). Like Berthe, Maillat was also a dabbler in the occult and black magic. She also saw herself as a seducer of writers: one of her other literary conquests was Leon Bloy (she would also later on become a mistress for Péladan, one of Huysmans’ enemies). Many of the love letters she wrote to Huysmans ended up being incorporated into

Là-Bas, which led to a bit of problems for Huysmans later on. A third influence on the character of Hyacinthe was Mme Charles Buet, the wife of Charles Buet (see below), though I’ve found little in the way of information in regards to this woman.

Madame Buet

Eugene Ledos

GEVINGEY: an astrologer and a “good Christian” who is a friend of Carhaix (he also eventually becomes a friend of both Durtal and des Hermies: in fact, he’s actually a patient of des Hermies). He appears in 37 of the book’s pages. Unlike most of the other characters in the book, he lives on the Right Bank of Paris, and is described as a short man with an egg-shaped head, faded brown hair, a shiny cranium, a hooked nose, a short chin, a toothless mouth, a thick mustache and goatee, close-set and slightly crossed eyes that resemble those of a startled bird, and a solemn voice. He dresses in a bizarre manner, and wears a number of large, strange rings on his hands. Though Durtal initially finds him pompous and conceited, he soon finds himself impressed by the man’s knowledge of astrology and that of incubi and succubae, along with other esoterica. His main function in the book (aside from letting Huysmans show off the fruits of his own research into astrology, incubi and succubae) is to describe the off-screen actions of Dr. Johannes and Canon Docre.

The real-life model for the character of Gevingey was Eugene Ledos, who was also an astrologer (as well as being a writer). I have found very little information about this man, aside from the names of some of his books and the above photograph. In the Baldick biography on Huysmans, there is but one mention of him in the entire book, and that’s only to let us know that Huysmans used to say (about Ledos) that “he looked as though he had been born with a three-legged stool fastened to his rump.” It is also believed by some that he once lived in an apartment above the Cabaret Voltaire.

![]()

DR. JOHANNES: a mystic, exorcist and doctor of theology. Dr. Johannes is a very interesting character. Even though he’s talked about a great deal in the text, he never actually physically appears, so all that we can rely on about him and his actions are the stories that other characters (chiefly Gevingey) tell Durtal about him. We learn that he lives in Lyons, that he preaches the coming of the Paraclete, that he’s a defrocked priest who specializes in curing “Satanic ailments,” and that he’s also mastered the lost art of ornithomancy (a form of divination involving the observation of the actions of birds). He is described as being a “super-being,” an ‘apostle animated by the Holy Spirit.”

Abbé Boullan, as has been previously noted, served as the primary model for Dr. Johannes. This was how Huysmans described Boullan to an unknown correspondent in early 1891: “He is a mystic of the wisest and most curious kind, preaching on the whole the dogmas of the early church of Lyons, of St. Ireanaeus and St. Pothinus, the coming of the Paraclete. He had devoted himself to the cure of evil spells, but had to give up, for not being a doctor of medicine but of theology he had trouble with both medics and ecclesiastics. Many stories have been told about him; he has been accused of black magic, etc. But I know the man sufficiently well to be able to affirm that they are absolutely false.” As we shall see, Huysmans was extremely wrong in this assessment of Boullan’s character, and appears to have been completely conned by the man and his followers.

CARHAIX’S WIFE: the wife of Carhaix, whose actual name is never given. She appears in 37 pages of the book, and is a somewhat minor character. An old woman from Landévennec, she lives with her husband in the bell tower of Saint-Sulpice, and like him she too is piously religious. Her main function in the novel is to cook and serve dinner to Durtal, des Hermies and Carhaix during their gatherings, though she does take part in some of the conversations as well (even more amazing is that her cooking finds favor with Durtal, who, like Huysmans, is a notoriously picky eater: here’s a description of one of his meals at a typical Paris restaurant of the time: “…he picked at a piece of stale fish, its flesh flabby and cold, dug out of its sauce some dead lentils, no doubt killed by insecticide. To finish, he savored some old prunes whose juice, smelling of mould, was both marshy and sepulchral.” And that’s from a restaurant that he found to be “fairly reliable.”!). Not much of a description of her is given; aside that she has a sickly and sincere face and candid and pitiful eyes.

![]()

![]()

Louis Van Haecke

CANON DOCRE: Canon Docre is the primary antagonist of

Là-Bas, the ideological opposite of Dr. Johannes. Like Johannes, we learn more about him and his actions through the dialogue of other characters, so he’s mostly an off-screen presence: he appears in a mere six pages of the book, within the Black Mass chapter, and doesn’t speak a single word to Durtal. And yet his shadow looms large throughout the story. Hailing from Nîmes, Hyacinthe describes Docre as being 40 years old and “good-looking,” but when he finally appears he’s described as being tall, ungainly, and top-heavy, with course and sinuous features, including shining eyes like small black apple pips, lips and cheeks covered in a thick, dense stubble, and a quavering, high-pitched voice. A man who likes to spend money, he lives in a tidy house, with its own lab and an immense library (one book that he keeps in this library is his Missal of the Black Mass, which is printed on parchment and whose binding is made from the skin of a child who had died unbaptized: stamped onto the front cover in a dried-flower fashion is a large host that had been consecrated during a Black Mass). The confessor of Hyacinthe, she also claims that he’s clever and charming, a gentleman and a scholar, (and formerly the confessor of an unnamed Royal Highness), though other characters in the book refer to him as the “incarnation of Evil on Earth,” and a few don’t like to even speak his name aloud (shades of Lord Voldemort from the

Harry Potter books, that). Like Dr. Johannes, he too is a defrocked priest (he was literally excommunicated by Rome), though where that former character uses his powers for good, Canon Docre uses his own considerable powers for evil. Aside from being a master hypnotist who can mesmerize people into committing suicide, he is also a necromancer who can invoke the spirit of a dead person and send it to kill his victims, along with being a mad scientist who has mastered the art of poisons: Huysmans describes how the Canon creates poisons by feeding either white mice or fish with consecrated Communion hosts and poison, before stabbing them over a chalice and draining the oils and fluids, the end product being used as a poison to drive men to insanity. But Canon Docre is most notorious for his reputation as a Satanist, and it is said he has the visage of the crucified Christ tattooed on the soles of his feet. A celebrant of the Black Mass and an invoker of the Devil, he truly is a diabolical creation, and has the honor of presiding over the novel’s notorious Black Mass scene.

The real-life model for Canon Docre was a Belgian priest named Louis Van Haecke, Chaplain of the Holy Blood at Bruges: like Canon Docre, it was rumored that he had a cross tattooed on the soles of his feet, “…so that he may have the pleasure of continually walking upon the symbol of the Saviour.” During the researching of

Là-Bas, Huysmans claimed to have witnessed a Black Mass, and during this Mass he said he spotted a cassocked priest also watching the event. Later on, he happened to spot a photograph of this same priest in the display window of an occult bookshop and recognized him as the man he thought he saw during the Black Mass. Huysmans would eventually confront Van Haecke and ask him what he was doing at a Black Mass, to which the priest replied, “Haven’t I the right to be inquisitive? And how do you know that I wasn’t there as a spy?” (It should be noted here that Van Haecke was supposedly an exceptionally inquisitive person with a strong interest in comparative religion).

Henry Chapnot’s illustration of Canon Docre from a 1912 edition of Là-Bas

Charles Buet

MONSIEUR CHANTELOUVE: the husband of Hyacinthe, he only appears in six of the book’s 278 pages, though his name does come up quite often. A Catholic historian who lives in a spacious apartment on the Rue de Bagneaux, he prides himself on the fact that his drawing room parties attract all manner of characters from different stratums of society: clergy members, poets, journalists, artists, actresses, occultists, and so on: “a curious mix of the grotesque and the refined,” as Huysmans puts it. At the time frame in which

Là-Bas takes place, he is writing a series dealing with the lives of the saints. Monsieur Chantelouve is described as a short and stout clean-shaven man with a huge pot belly, ruddy cheeks, and over-pomaded hair. It is said in the book that he is cordial, vigorous, generous, and good-natured, but at the same time he has a slightly sinister air about him: Durtal finds his eyes to be “sly and deceitful,” and that he has the look of a “scheming, cunning businessman who, despite his honeyed manner, was capable of the most underhand dealings.” Indeed, it is hinted that he is involved in some dodgy financial dealings on the side. Some of his books include a history of Poland and a biography on Pope Boniface.

The real-life model for Monsieur Chantelouve was Charles Buet (b. 1846, d. 1897), a Catholic historian and writer of historical novels that has been all but forgotten in today’s times. Like his fictional counterpart, Buet was well known for the literary salons he held at his place in the Avenue de Breteuil, these salons attracting such writers as Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly, Leon Bloy, Jean Lorrain, and, of course, Huysmans himself. He seemed to have had a slightly sinister reputation as well: Jules Renard described Buet as “Catholicism at its greasiest and dirtiest.” Despite the highly unflattering portrayal of man that Huysmans paints in his novel, Buet evidently harbored no ill-will towards Huysmans, and the two remained friends for the rest of Buet’s life: Huysmans attended his funeral in 1897. Buet’s chief criticism of

Là-Bas appears to have been his taking issue with Huysmans’ description of the notorious Cantianille affair that scandalized the city of Auxerre in 1865, a description that Buet pointed out was “altogether inaccurate” (to quote from a letter that Buet sent to Huysmans on April 15th, 1891, shortly after the book’s publication).

RATEAU: a drunken and elderly mustachioed lout who is also the concierge of Durtal’s apartment building, one of whose tasks includes cleaning Durtal’s apartment every week: ironically, by the time that Rateau finishes his cleaning the apartment is usually messier then before he began, which infuriates Durtal. Rateau only appears on 4 pages and essentially serves as a bit of comic relief.

the above illustration is taken from a 1912 edition of Là-Bas

“Guibourg’s efforts to convince La Reynie that he and la Voisin had seen very little of each other were undermined by the fact that Marie Montvoisin was able to conjure up the most lurid memories of things that he and her mother had done together. On 9 October she made her most sickening declaration to date. She said that she had been present when Guibourg had performed a black mass on Mme de Montespan and that, during this ceremony, her mother had instructed her to hand Guibourg a newly born baby. Guibourg had cut the child’s throat and collected its blood in a chalice. At the appropriate point in the ceremony he elevated this vessel and the blood took the place of the sacramental wine. When the mass was over, Guibourg had torn out the butchered infant’s entrails and given them to la Voisin so she could have them distilled. The blood had been poured into a phial and carried away by Mme de Montespan.”

-Anne Somerset,

The Affair of the Poisons Là-Bas: The Writing ProcessBefore I begin to examine in detail the construction of

Là-Bas, it might be conductive to first offer a brief examination of Huysmans’ literary career up to the year 1887. Born in 1848, Huysmans made his literary debut at the age of 26 in 1874 when he self-published a collection of prose poems and short sketches entitled

Le drageoir aux épices. I haven’t read this book myself yet (as far as I know it hasn’t been translated into English, though I might be mistaken here), though I’ve heard it owes a great debt to Charles Baudelaire’s

Paris Spleen. Although this book was virtually ignored by the reading public of that time, it brought him to the attention of some of the leading literary figures of his day. In 1876 Huysmans began to befriend writers such as Zola and Guy de Maupassant (I have a confession to make here: I’ve never read a word of Zola), and soon enough he was hanging out with other writers such as Flaubert and the Goncourt brothers. 1876 also saw the publication of

Marthe, histoire d’une fille, a short and downbeat novel about a Parisian prostitute that earned him a fair bit of notoriety. In 1879 Huysmans’ second (and most conventionally Naturalistic) novel,

Les Soeurs Vatard, was published. This book revolved around the unhappy love lives of two female bookbinders, and of all the Huysmans novels that I’ve read I would classify it as perhaps his weakest work. In 1882 Huysmans’ last true Naturalistic novel,

A Vau-l’Eau (

Downstream in English), was released, this being a brief and gleefully pessimistic novel about the daily miseries of a clerk (it should be noted this book owes a lot to the philosophy of Schopenhauer: it should also be noted that in real life Huysmans himself was a clerk for the Ministry of the Interior, a national criminal investigative bureau, a position he would hold for 32 years. Incidentally,

Là-Bas’ manuscript was written out on notepaper supplied by the Ministry, and that according to Remy de Gourmont Huysmans would often work on it during office hours).

Huysmans’ break with the Naturalist school of writing began in 1884, with the publication of

A Rebours (

Against Nature or

Against the Grain in English), a book that is widely considered both a classic and Huysmans’ masterpiece, and which is so well-known today that little needs to be said on it (even if many people only know of it in a secondhand manner from Oscar Wilde’s

The Picture of Dorian Gray, which was heavily inspired by Huysmans’ novel and makes a number of thinly veiled allusions to it). It will suffice to say that in my opinion

A Rebours is possibly the most groundbreaking, modern, and important book to come out of the 19th-century. One thing that amazes me about Huysmans is that, even though in some respects he was a little backwards (see his extreme misogyny), at the same time he was one of the first art critics to recognize (and champion) the importance of the Impressionist and Symbolist art movements; likewise, he was one of the first literary men of his day to acclaim the poetry of Verlaine and Mallarmé. I find it especially exciting that, in regards to his own work, Huysmans was well aware of the new ground that he was breaking in regards to the medium of the novel: during the writing of A Rebours, he wrote a letter to a friend boasting that his new novel was “a book that would astonish the world, a book beyond anything that had yet been conceived.” Early English translations of the book often made mention, on its cover, how it was “a novel without a plot!”

In 1886, Huysmans backpedaled a bit from the radical path he took with

A Rebours with the publication of his sixth novel, the underrated and sadly neglected

En Rade (

A Haven or

Stranded in English), which juxtaposed the story of Parisian city-dwellers visiting the countryside with bizarre and evocative dream scenes (that were largely influenced by Huysmans’ appreciation of the then vogue Symbolist art movement, in particular the work of Odilon Redon).

By the time he had finished

En Rade, Huysmans found himself at a literary dead-end, sick of writing novels in the conventionally Naturalist vein but unsure in which direction he should go next. And thus did he begin investigating subjects such as the occult and alchemy, in the hope of finding something new to write about. As Édouard Dujardin once remarked about Huysmans’ 1887 period, “I was struck by the importance which Huysmans attached, not yet to things religious, but to what I shall call things of mystery - in other words, anything transcending the tangible and the rational. He used to tell us weird stories of secret cults, of werewolves and witchcraft and satanism; and he would usually conclude by saying, after a long pause: ‘It’s all very strange… very strange…’.” And in 1887, to his friend Gustave Guiches, Huysmans said, “…I want nothing more to do with that naturalistic filth! So what remains?... Perhaps there’s still occultism. I don’t mean spiritualism, of course - the cheap swindlers with their shady tricks, the mediums with their buffoonery, and the doddering old ladies with their table-turning antics. No, I mean genuine occultism - not above but beneath or beside reality! Failing the faith of the Primitive or the first communicant, which I should dearly love to possess, there’s a mystery there which appeals to me. I might even say that it haunts me…”

![]()

Stanislas de Guaita

Huysmans’ growing fascination with the occult led him to explore some of the occult circles and bookstores of Paris (such as Edmond Bailly’s notorious occult bookshop Librairie de l’Art Indépendant, located at 9 Rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin: this bookstore was also a popular haunt for writers and artists such as Arthur Rimbaud, Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Stéphane Mallarmé), where he met a number of bizarre personalities, including the Marquis Stanislas de Guaita (a French poet, morphine addict and occult novelist who had revived the Rosicrucian Order in Paris, and who today is perhaps best known as the creator of the “goat pentagram”), Paul Adam (a novelist and member of the Supreme Council of the Rosy Cross), and Jules Bois (a young man who was just beginning to write a book entitled

Le Satanisme et la magie). And it was these investigations that led him to the Naundorff cause. Charles Naundorff had appeared in the city of Paris in the year 1833, whence he claimed to be the son of Louis XVI (who had been beheaded in 1793) and also the Duke of Normandy. Such claims earned him the support of assorted occult groups, secret societies, and fringe members of the Bourbon legitimist movement.

On October 31st, 1887, Huysmans wrote to Zola that he was working on a novel dealing with “…the fringe of the clerical world and the followers of good King Charles XI… a set of cranks I’ve been watching for some years.” And on November 30th, 1887, Huysmans went into a bit of detail regarding his new book in a letter to the Belgian art critic and lawyer Jules Destrée: “I am immersed in an enormous job in preparation for my novel about the fringes of the clerical world and the cause of King Charles XI (Naundorff). You cannot imagine the reading I have had to do, hagiography, alchemy, Mattei’s medicine; the history of the later Roman Empire, stacks of brochures and newspapers on the survival of Louis XVII. I am exhausted by it. Now I have to put it all together, and get down to work. I sweat at the thought of it - but if I could bring it off, it would be a curious book, set in an uncharted world, a book with some very strange flights of imagination and some atrocious realities - the whole lot to be acclaimed as a flop, a huge flop, as far as the reading public is concerned.”

Very little information is known to us as to the details of this Naundorff novel, and no one has ever figured out his reasons for abandoning it (he most likely quit it in the fall months of 1888, or perhaps shortly before then, though this is conjecture on my part); all that is known was that it was supposedly to have been a “complex political novel, a tale of intriguing eccentrics, of plot and counterplot” (to use Robert Baldick’s description of it). It has been conjectured (again, by Baldick) that a primary reason could have been his adoption of a “new artistic formula” which he first adopted in 1888. That summer (in August, to be precise), Huysmans had discovered Matthias Grünewald’s

Crucifixion in the Museum at Cassel, a work of art that inspired him to create what he came to call “Spiritual Naturalism” (also known as “supernatural realism”). Retaining the documentary technique of the Naturalists (while discarding what he saw as their “gross materialism”), Huysmans would eventually provide a definition of Spiritual Naturalism in the first chapter of

Là-Bas:

“It was necessary to keep the accurate documentation, the precision of detail, the rich and vigorous style of the Realists; but it was also necessary to sink well-shafts into the soul, instead of trying to explain its every mystery by some malady of the senses. The novel, if that were possible, ought to be divided into two parts – that of the soul and that of the body – which would be welded together, or rather intermingled, as they are in life; and it should tell of their mutual reactions, their conflicts, their points of agreement. In a word, the novelist must follow the highway so strongly marked out by Zola; but he should also trace a parallel road in the air, a second highway reaching out to regions beyond and hereafter; he should, in fact, fashion a spiritual naturalism that would be far finer, more powerful, and more complete!”

(So impressed was Huysmans with Grünewald’s

Crucifixion that he would later on write about it at length in the first chapter of

Là-Bas: see below).

Sometime in-between April of 1888 and the start of 1889 Huysmans began to work on a new novel, this one set during the Middle Ages and dealing with the life and crimes of Gilles de Rais (in a letter to Jules Destrée written in April of 1888, Huysmans wrote, “Là-bas a été commencé, à pein,” which translates to something like “

Là-Bas has been started,” thus indicating that this was Huysmans’ preferred name for the book from the very beginning). After many months of research (his main source in this regards was Eugène Bossard’s 1886 study

Gilles de Rais, maréchal de France, dit “Barbe-Bleue”), Huysmans decided that a bit of field research was in order. During the summer months of 1889, when most of his peers in the civil service were no doubt vacationing in France’s assorted coastal resorts, Huysmans was spending his leisure time in the ruins of Gilles de Rais’ castle, the notorious Château de Tiffauges, ostentatiously for research purposes (this castle being located near the border of Brittany). In a letter he wrote to Odilon Redon on September 15th, 1889, Huysmans wrote, “The ruins of his castle are wonderful, and each dungeon one opens still contains the bones of children whom he raped and murdered whilst invoking the Devil! It is superb!” It should be noted here that Huysmans had a tendency to exaggerate his stories for dramatic effect, and this could be a good example of that. Here’s Edmond de Goncourt’s description of Huysmans’ time at Tiffauges: “Huysmans amused himself by troubling Poictevin’s feeble wits with his Mephistophelism, looking in the latrines of a ruined castle for the remains of children slaughtered by Gilles de Rais, and for want of better booty, carrying off a priest’s caecum which they found in a monastery graveyard.” In any case, this trip found Huysmans in an extremely jovial mood, though his happiness dispersed upon returning to Paris later that month (see his letters to Redon and Verlaine below).

![]()

part of the ruins of Tiffauges

Around this same period of time (late 1889), the novel that was to become

Là-Bas underwent a further permutation, when Huysmans decided to adopt a binary structure for it (this ‘binary novel’ idea no doubt inspired by the 1889 book

Un Caractere, by his friend Leon Hennique). Just as that book alternated scenes from two different eras, both past and present, so would

Là-Bas now become a study of both contemporary and medieval Satanism, which he described as “…a parallel demonstration that the same spiritual phases occur in the same sequence – that they have not changed in character but have merely been cloaked by hypocrisy.” One reason why Huysmans adopted this plan was so that now he could make use of both his researches into the topic of Gilles de Rais (medieval Satanism) but also his researches into modern-day occultism (see the abandoned Naundorffist novel).

Determined to prove to himself that Satanism still existed in modern France, Huysmans began to meet practicing Satanists. He was also determined to witness a Black Mass. Whether Huysmans ever did witness such a thing has still yet to be proven, and it doesn’t help matters that at some points of his life Huysmans has said that he did, while at other times he has denied it. Remy de Gourmont has stated that the Black Mass chapter in

Là-Bas was the product of Huysmans imagination, and Abbé Arthur Mugnier (Huysmans’ first spiritual director) also claimed that Huysmans had never witnessed an actual Black Mass (in March of 2015, I e-mailed Brendan King asking him a number of questions related to

Là-Bas, chief among them being his own opinion as to if Huysmans had actually attended such a ceremony: personally, he doubted it himself). It might interest some people on this blog to know that Georges Bataille, in his book

Eroticism: Death & Sensuality writes the following: “The Black Mass attended by Huysmans, described in

Là-Bas, is indisputably authentic” (in his book

The Occult, Colin Wilson also makes the following observation: “The black mass scene is obviously the high point of the novel. It has a remarkable feeling of authenticity”). Whatever the real case may be, it’s worth noting that the actual ceremony itself (as described in

Là-Bas) is actually based on papers that Huysmans obtained through the Vintrasian archives (courtesy of Boullan) and also on famous historical Black Masses, such as those practiced by Guibourg and Madame Montespan during the Affair of the Poisons.

It is at this point now that Abbé Boullan enters the story.

Huysmans first became aware of Boullan’s name towards the end of 1889. By this point in time, Boullan had something of a notorious reputation in France, to the extent that Guaita summed him up thusly: “a pontiff of infamy, a base idol of the mystical Sodom, a magician of the worst type, a wretched criminal, an evil sorcerer, and the founder of an infamous sect.” Joseph-Antoine Boullan was born on February 18th, 1824, in the village of Saint-Porquier. At an early age, Boullan knew he wanted to become a priest, and after doing some of his studies at the local seminary he eventually traveled to Rome to earn his doctorate. Following that achievement, he joined the Missionaries of the Precious Blood and got involved with a number of missions in Italy before settling down in a Society house near Turckheim in 1853. In 1855, he became the superior of this establishment, only to leave in 1856 under mysterious circumstances. He then moved to Paris to serve as an independent priest, where he began editing his first periodical,

Les Annales du Sacerdoce (Annals of the Priesthood). That same year he was entrusted with the spiritual direction of a nun named Adele Chevalier (who, in 1856, had undergone a miraculous cure that she credited to the intercession of Our Lady of La Salette).

In 1859, Boullan and Chevalier founded a religious community known as the Society for the Reparation of Souls at Bellevue. By this point in time, the relationship between Boullan and his protégé had turned sexual, and they began to carry out a number of sacrilegious practices. Supposedly on December 8th, 1860, Boullan ended a Mass by ritually sacrificing a child on the altar, this child having been born by Chevalier at the moment of Consecration. Though this crime was never reported to the police, a number of complaints about the Society came to the attention of the Bishop of Versailles, who put both Boullan and his mistress on trial for fraud and indecency in 1861. Found guilty on the first count, Boullan was sentenced to three years of prison, which he served at Rouen from December 1861-September 1864. He was imprisoned again in 1869, this time at Rome, in one of the cells of the Holy Office (which was the Inquisition’s name for itself at that time: intriguingly, Boullan went to them voluntarily). On May 26th, 1869, he began to write a confession of his crimes, and this document came to be known as the

cahier rose. Little is known about this sinister document, other than that its contents have been described as “shocking” and “horrifying.” Huysmans himself would read it towards the end of the 19th-century, and it later fell into the hands of Professor Louis Massignon, who in turn delivered it to the Vatican in 1930. Today, it resides in that forbidden library known as the

Archivum Secretum Apostolicum Vaticanum (Vatican Secret Archives), and all applications to see it are supposedly refused (well, according to the internet, that is, so take all of this with a grain of salt).

Upon being rehabilitated by the Holy Office, Boullan returned to Paris in the winter of 1869 and, in January 1870, began issuing a new periodical,

Annales de la sainteté au XIXe siècle. Within this periodical he espoused a number of heretical views that brought him to the attention of the Cardinal Archbishop of Paris. Rumors had also begun to circulate that Boullan had begun indulging in his diabolical practices again, using his reputation as an exorcist as a cover: Boullan was often entrusted to convents to help exorcise nuns who complained of demonic visitations, but besides just exorcising said nuns, Boullan also “…taught them how, by means of auto-hypnosis and auto-suggestion, they could dream that they were having intercourse with the saints or with Jesus Christ, and showed them what postures and occult methods they should adopt to enable supernatural entities – and more particularly his own astral body – to visit and possess them…”

In 1875, the Archbishop of Paris summoned Boullan to his Palace. During this meeting, Cardinal Guibert condemned Boullan’s doctrines, placed him under a solemn interdiction, and ordered him out of the Palace. Boullan fruitlessly appealed to Rome to reverse this interdict, but the Vatican decided to uphold the Cardinal’s judgement. And thus did Boullan leave the Church in July of 1875. That very month, he entered into correspondence with Pierre Vintras, the so-called miracle worker of Tilly-sur-Seulle who claimed he was a reincarnation of the prophet Elijah (and who believed it was his mission in life to prepare Earth for the Era of the Paraclete, the coming of the Christ of Glory: it should also be observed here that he was a supporter of the Naundorff claim). They first met in person in Brussels on August 13th, 1875, and again on October 26th, 1875, this time in Paris. Their friendship didn’t last long, for Vintras passed away on December 7th, 1875. Boullan then announced that Vintras had chosen him to be his successor. And so he became high priest of the Vintrasian sect and leader of the Society of Mercy.

![]()

Pierre Eugène Vintras

In February of 1876, Boullan moved to Lyons, mainly to study the papers left behind by Vintras and familiarize himself with its spiritual jargon. It was around this time that Boullan proclaimed himself as the reincarnation of John the Baptist, and to celebrate the occasion he had a cabbalistic pentagram tattooed at the corner of his left eye. However, his ascendency of the Vintras sect wasn’t without controversy, as a sizeable number of its members were suspicious of his speedy conversion: only 3 of the 19 pontiffs consecrated by Vintras accepted Boullan as their new leader. Indeed, I’ve recently read a number of conspiracy theories that put forth the notion that Boullan’s dismissal from the Church was a false story, and that, acting as a spy on behalf of the Vatican, he was tasked with infiltrating the Vintras sect and undermining it from within (certainly it seems slightly suspicious how Vintras died so quickly after making Boullan’s acquaintance). I suppose that would make Boullan some kind of secret agent of the clerical world. In any event, Boullan situated his headquarters in Lyons, in 1884, at No. 7 Rue de la Martiniere, which was the home of an architect named Pascal Misme, known in the Boullan sect (somewhat pompously) as ‘Pontiff of the Divine Melchizedean Chrism.’

Boullan’s teachings primarily revolved around the idea that, since it was sex that led to the Fall of Adam and Eve (and, following that train of thought, all of humanity), it was by sex that man could achieve salvation, mainly by having sexual intercourse with people on a higher spiritual level than oneself (which in turn would raise the celebrant to that same level). Or to use his own words, “…since the Fall of our first parents was the result of an act of culpable love, it was through acts of love accomplished in a religious spirit that the Redemption of Humanity could and should be achieved.” Which explains why the rites created by Boullan (known as his “Unions of Life”) involved hallucinatory sexual acts with Jesus, the Virgin Mary, the saints, angels, and so forth. And because Boullan was on a higher spiritual plane than the female members of his cult, he could often convince these woman to have sex with him, and thus elevate them to a higher spiritual level (this, of course, being a tried and true tactic of many cult leaders… just look at Charles Manson). As Robert Irwin notes in his afterward to the Dedalus edition of

Là-Bas, “Boullan and his followers also experimented in astral sex with incubi and succubi, and Boullan was supposed to have coupled with half-human creatures on the astral plane in order to raise them to a fully human form.”

Although Boullan went to great lengths to shield these ‘unions’ from the eyes of the profane, in 1886 he made the mistake of taking into his confidence three strangers: Canon Roca (a socialist priest with an interest in the occult), Stanislas de Guaita, and Oswald Wirth, the latter being a Swiss occultist and Rosicrucian (and who today is best known for his creation of the ‘Arcanes du Tarot kabbalistique’ Tarot deck in 1889). Wirth spent a year under the tutelage of Boullan, shamelessly kissing ass until, in December of 1886, he managed to obtain a written statement of Boullan’s “secret doctrine.” He then left Boullan’s sect and wrote him a mocking letter telling him how he had been hoodwinked. Guaita and Wirth compared notes in early 1887, then enacted a tribunal of sorts that found Boullan “guilty.” They sent a letter to Boullan telling him that he was now a condemned man. Boullan took this as a death threat and concluded that the two occultists intended to assassinate him via magical methods. For their part, Wirth and Guaita claimed that they simply intended to expose Boullan’s secrets to the public, which they did in 1891 with the publication of their book

Le Temple de Satan.

Oswald Wirth as a young man

On February 2nd, 1890, Huysmans wrote a letter to Oswald Wirth, stating: “In connection with a book I am writing, I need certain information on the modern practices of Satanism. The Reverend Canon Roca, who is in the Pyrenees at the moment, expressly requests that I do not contact Fr Boullan directly, as he considers him dangerous, and he authorizes me to use his name in asking you for a meeting at which I could talk to you about this Satanist, with whom you had dealings at the same time as himself.” Oswald replied back that “…all the information I possess concerning the person you mention, being only too happy if I can help you to put our contemporaries on guard against the most dangerous of all human aberrations.” Huysmans met with Wirth at the latter’s flat on February 7th, 1890, but found himself unimpressed with both Wirth’s information and also Wirth himself. Although Wirth tried to dissuade Huysmans from contacting Boullan, little did he know that Huysmans had already sent out a letter to Boullan two days earlier, on the 5th of February (Berthe de Courrière, ever helpful, had supplied Huysmans’ with Boullan’s mailing address in Lyons).

In this letter to Boullan, Huysmans wrote the following: “Several times I heard your name pronounced in tones of horror – and this in itself predisposed me in your favour. Then I heard rumours that you were the only initiate in the ancient mysteries who had obtained practical as well as theoretical results, and I was told that if anyone could produce undeniable phenomena, it was you and you alone. This I should like to believe, because it would mean that I had found a rare personality in these drab times – and I could give you some excellent publicity if you needed it. I could set you up as the Superman, the Satanist, the only one in existence, far removed from the infantile spiritualism of the occultists. Allow me, then, Monsieur, to put these questions to you – quite bluntly, for I prefer a straightforward approach. Are you a satanist? And can you give me any information about succubi – Del Rio, Bodin, Sinistrari and Gorres being quite inadequate on this subject? You will note that I ask for no initiation, no secret lore – only for reliable documents, for results you have obtained in your experiments…”

On February 6th, 1890, Boullan wrote back to Huysmans, in which he refused the publicity offered by Huysmans and denied being a Satanist: lying through his teeth, he described himself as “an Adept who has declared war on all demoniacal cults.” He also (truthfully) claimed to be an authority on incubi and succubi, but steadfastly refused to give Huysmans any more information until Huysmans went into more detail on the purposes of his inquiries. He signed his letter “Dr. Johannes,” which was his “Adept’s name,” and which would also be the name that Huysmans would refer to him as in

Là-Bas.

On February 7th (the same day that Huysmans met with Wirth), Huysmans wrote Boullan a second letter, assuring him that his book would not glorify Satanism, but instead prove its continued existence in the world: “It happens that I’m weary of the ideas of my good friend Zola, whose absolute positivism fills me with disgust. I’m just as weary of the systems of Charcot, who has tried to convince me that demonianism was just an old wives’ tale, and that by applying pressure to the ovaries he could check or develop at will the satanic impulses of the women under his care at La Salpêtrière. And I’m wearier still, if that be possible, of the occultists and spiritualists, whose phenomena, though often genuine, are far too often identical. What I want to do is teach a lesson to all these people – to create a work of art of a supernatural realism, a spiritual naturalism. I want to show Zola, Charcot, the spiritualists, and the rest that nothing of the mysteries which surround us has been explained. If I can obtain proof of the existence of succubi, I want to publish that proof, to show that all the materialist theories of Maudsley and his kind are false, and that the Devil exists, that the Devil reigns supreme, that the power he enjoyed in the Middle Ages has not been taken from him, for today he is the absolute master of the world, the Omniarch…”

Replying back on February 10th, 1890, Boullan now expressed satisfaction with Huysmans’ intentions, and agreed to help him in any way that he could. He wrote back, “I can put at your disposal documents which will enable you to prove that satanism is active in our time, and in what form and in what circumstances. Your work will thus endure as a monumental history of satanism in the nineteenth century.” On this last point, Boullan was certainly on the mark, for even today the cult of

Là-Bas lives on! True to his word, Boullan began to mail a steady stream of documents to Huysmans’ flat, giving him a lot of information on succubi, the art of spellcasting, the Sacrifice of the Glory of Melchizedek, the Black Mass, and so on.

On February 13th, 1890, Wirth sent Huysmans a letter referring to passages from a book which dealt with the criminal activities of Boullan’s Society for the Reparation of Souls. A few weeks after that, Wirth and a friend would visit Huysmans office at work, where they described to him the obscene practices and ‘secret doctrine’ of Boullan’s sect in Lyons, but Huysmans refused to take them seriously. As Wirth later recalled: “He listened to us with a smile on his lips, and then remarked that if the old man had found a mystical dodge for obtaining a little carnal satisfaction, that surely wasn’t so stupid of him…”

On February 19th, 1890, Huysmans wrote a letter to the Dutch industrialist Arij Prins, writing, “I am in regular correspondence with that sacrilegious priest who invokes succubi in Lyons. He sends me documents on Satanism in our times; it is curious. I shall probably go and see him in the Easter holidays. I hope to use all this to produce a book that will embarrass our foolish contemporaries, for it emerges from our certified documents that black masses have continued to be said since the Middle Ages. In the seventeenth century, a certain Fr Guibourt celebrated it on the stomach of Mme de Montespan, and it is still going on today; there are sympathizers who indulge in sacrilege throughout Europe and even in America, where the poet Longfellow was head of a sect. All that gets rather involved with sodomy, as you can imagine. In this connection I have made a few sorties into the world of these ‘pearls,’ but despite everything, I do not find these mustachioed types seductive. Ah, if only your skater…! But he is already sufficiently perverted, from what you tell me.”

(Note: in Huysmans’ day, the word ‘pearl’ was a slang term for a homosexual. The ‘skater’ in this letter is an attractive young man that Prins was sexually obsessed with at that time, a topic that seemed to fascinate Huysmans himself. In another letter to Prins, Huysmans writes “Decidedly I am not a sodomite, a pederest maybe, with a young boy clean-shaven, but with these hulking mustachioed fellows 30 years old, nothing happens.” The reference to Longfellow is one of the mistakes that Huysmans made in the novel. In chapter V of

Là-Bas, he writes, “There are now committees and sub-committees, a kind of Satanic court with jurisdiction over America and Europe, just like the Curia of the Pope. The largest of these societies, which dates from 1855, is the Society of Aristocratical Neo-Theurgists. It is split, despite an appearance of unity, into two camps: one aspiring to destroy the universe and reign over the ruins, and the other dreaming simply of imposing a demonic cult on the world, of which it would be the high priest. The society is based in America and was formerly under the direction of Longfellow, who styled himself the High Priest of New Evocative Magic, and for a long time now it has also had branches in France, Italy, Germany, Russia, Austria and even Turkey. At the present time, it’s pretty much on the wane or perhaps even defunct altogether, but another is on the way to being formed, the intention of which is to elect an anti-pope who will be the exterminating Antichrist.” Huysmans was under the mistaken believe that this was the poet Longfellow, rather than an occultist/Satanist of the same name!).

On June 15th, 1890, Huysmans wrote a letter to Arij Prins, reporting on the progress of his novel (among other subjects): “As for my book, I am working hard at it, terribly hard, but I am in despair. The warp is too close, the slotting together of Gilles de Rais and Satanism in our day is very simple, it does it all by itself. But… but… the frightening aspect is the grey tone of this book. It consists of conversation and dialogue. There are times when it takes on the appearance of theatre, and there is no way of doing it differently! It has not got the gleam of my other books at all; it is dull and cold. I have moments when I am discouraged by it. I do hope that this book, which is all episodic, will achieve a strange and curious whole, but that will be a question of chance, for nothing is less sure! Oh documentation! There is so much of it in this book, that there is no way I can turn it into art!” In this same letter he inquires again about Prins’ skater and encourages him to engage in a bit of anal sex: “Your little skater sometimes makes me dream. I should prefer him to the Countess. All the more so as he seems ripe for carnal sin. Come my friend, a little courage, deflower the mouth of Sodom!”

On July 24th, 1890, Huysmans once again sent a letter to Arij Prins, where he wrote: “…I have been condemned to death by the Rosicrucians, one of the recent Satanic sects founded in France!!! In magic any secret revealed is lost, and they are trying to stop my book coming out. Needless to say that, despite the sympathetic magic and poisonings aimed at my person, I am quite well! Fr Boullan, it is true, maintains he is defending me against them. It is quite laughable.” In the same letter he also wrote about how “My book will also have in its favour that it will be the final dismantling of that crumbling mound known as naturalism!” That same month, on June 26th, 1890, Huysmans wrote a letter to Boullan informing him that

Là-Bas was now two-thirds finished.

Huysmans most likely completed

Là-Bas in September of 1890. That same month he made the acquaintance of an older woman known as Julie Thibault, a priestess of Boullan’s sect and also his housekeeper (she would, in later years, briefly serve as Huysmans’ housekeeper as well). Thibault (whose nickname was ‘The Apostolic Woman”) was something of a Christian mystic who claimed to have conversations with the saints and the Virgin Mary every day. Needless to say, Huysmans found her fascinating, and she would go on to provide inspiration for his Madame Bavoil character in his later novels (namely

The Cathedral and

The Oblate). On the night of his introduction to Thibault, Huysmans was paid a visit by a succubus, which he believed was sent to him by Thibault: he described the experience as being “both exquisite and painful.” It was this event that convinced him the time was right to finally meet Boullan in person (a brief note: this wouldn’t be the first time that Huysmans was plagued by a succubus: during his stay at the monastery Notre-Dame d’Igny in the summer of 1892 he also claimed to be tormented by such beings).

Julie Thibault

In late September/early October, Huysmans visited Lyons to finally meet Boullan in person and thank him for his help with the research of

Là-Bas.

On October 11th, 1890, Huysmans wrote a letter to Georges Landry in which he insisted that Boullan was “…not a Satanist – that is for certain – but he is the most extraordinary miracle worker in existence! I have been cosseted by these good people in a way I could not have expected. I have also seen singular things, and to think that there are people who deny the existence of the mysterious!”

In a letter to Jules Destrée written on December 12th, 1890, Huysmans wrote, “I have finished my book on Satanism, which is enormous (five hundred tightly packed pages!). I hope to come out in the first few months of next year. I expect nothing from it, I shall be accused of mystification or madness, and no one will believe that the strangest documents in this book were given to me by a priest, the last exorcist to be in possession of the secrets of the Middle Ages.”

January of 1891 found Huysmans going over the proofs of

Là-Bas, as he relates in a letter to the bookseller/police-spy Gustave Boucher on January 15th, 1891 (it was Boucher who supplied Huysmans with some details on the Mass of Melchizedek, back in September of 1890, when they first made each other’s acquaintance).