1.THE PLANET TRILLAPHON AS IT STANDS IN RELATION TO THE BAD THING.

I've been on antidepressants for, what, about a year now, and I suppose I feel as if I'm pretty qualified to tell what they're like. They're fine, really, but they're fine in the same way that, say, living on another planet that was warm and comfortable and had food and fresh water would be fine: it would be fine, but it wouldn't be good old Earth, obviously. I haven't been on Earth now for almost a year, because I wasn't doing very well on Earth. I've been doing somewhat better here where I am now, on the planet Trillaphon, which I suppose is good news for everyone involved.

Antidepressants were prescribed for me by a very nice doctor named Dr. Kablumbus at a hospital to which I was sent ever so briefly following a really highly ridiculous incident involving electrical appliances in the bathtub about which I really don't wish to say a whole lot. I had to go to the hospital for physical care and treatment after this very silly incident, and then two days later I was moved to another floor of the hospital, a higher, whiter floor, where Dr. Kablumbus and his colleagues were. There was a certain amount of consideration given to the possibility of my undergoing E.C.T., which is short for "Electro Convulsive Therapy,' but E.C.T. wipes out bits of your memory sometimes - little details like your name and where you live, etc. - and it's also in other respects just a thoroughly scary thing, and we - my parents and I - decided against it. New Hampshire, which is the state where I live, has a law that says E.C.T. cannot be administered without the patient's knowledge and consent. I regard this as an extremely good law. So antidepressants were prescribed for me instead by Dr. Kablumbus, who can be said really to have had only my best interests at heart.

If someone tells about a trip he's taken, you expect at least some explanation of why he left on the trip in the first place. With this in mind perhaps I'll tell some things about why things weren't too good for me on Earth for quite a while. It was extremely weird, but, three years ago, when I was a senior in high school, I began to suffer from what I guess now was a hallucination. I thought that a huge wound, a really huge and deep wound, had opened on my face, on my cheek near my nose .. . that the skin had just split open like old fruit, that blood was seeping out, all dark and shiny, that veins and bits of yellow cheek-fat and red-gray muscle were plainly visible, even bright flashes of bone, in there. Whenever I'd look in the mirror, there it would be, that wound, and I could feel the twitch of the exposed muscle and the heat of the blood on my cheek, all the time. But when I'd say to a doctor or to Mom or to other people, "Hey, look at this open wound on my face, I'd better go to the hospital," they'd say, "Well, hey, there's no wound on your face, are your eyes OK?" And yet whenever I'd look in the mirror, there it would be, and I could always feel the heat of the blood on my cheek, and when I'd feel with my hand my fingers would sink in there really deep into what felt like hot gelatin with bones and ropes and stuff in it. And it seemed like everyone was always looking at it. They'd seem to stare at me really funny, and I'd think "Oh God, I'm really making them sick, they see it. I've got to hide, get me out of here." But they were probably only staring because I looked all scared and in pain and kept my hand to my face and was staggering like I was drunk all over the place all the time. But at the time, it seemed so real. Weird, weird, weird. Right before graduation - or maybe a month before, maybe - it got really bad, such that when I'd pull my hand away from my face I'd see blood on my fingers, and bits of tissue and stuff, and I'd be able to smell the blood too, like hot rusty metal and copper. So one night when my parents were out somewhere I took a needle and some thread and tried to sew up the wound myself. It hurt a lot to do this because I didn't have any anesthetic, of course. It was also bad because, obviously, as I know now, there was really no wound to be sewn up at all, there. Mom and Dad were less than pleased when they came home and found me all bloody for real and with a whole lot of jagged unprofessional stitches of lovely bright orange carpet-thread in my face. They were really upset. Also, I made the stitches too deep - I apparently pushed the needle incredibly deep - and some of the thread got stuck way down in there when they tried to pull the stitches out at the hospital and it got infected later and then they had to make a real wound back at the hospital to get it all out and drain it and clean it out. That was highly ironic. Also, when I was making the stitches too deep I guess I ran the needle into a few nerves in my cheek and destroyed them, so now sometimes bits of my face will get numb for no reason, and my mouth will sag on the left side a bit. I know it sags for sure and that I've got this cute scar, here, because it's not just a matter of looking in the mirror and seeing it and feeling it; other people tell me they see it too, though they do this very tactfully.

Anyway, I think that year everyone began to see that I was a troubled little soldier, including me. Everybody talked and conferred and we all decided that it would probably be in my best interests if I deferred admission to Brown University in Rhode Island, where I was supposedly all set to go, and instead did a year of "Post-Graduate" schoolwork at a very good and prestigious and expensive prep school called Phillips Exeter Academy conveniently located right there in my home town. So that's what I did. And it was, by all appearances, a pretty successful period, except it was still on Earth, and things were increasingly non-good for me on Earth during this period, although my face had healed and I had more or less stopped having the hallucination about the gory wound, except for really short flashes when I saw mirrors out of the corners of my eyes and stuff.

But, yes, all in all things were going increasingly badly for me at that time, even though I was doing quite well in school in my little "PostGrad" program and people were saying, "Holy cow, you're really a very good student, you should just go on to college right now, why don't you?" It was just pretty clear to me that I shouldn't go right on to college then, but I couldn't say that to the people at Exeter, because my reasons for saying I shouldn't had nothing to do with balancing equations in Chemistry or interpreting Keats poems in English. They had to do with the fact that I was a troubled little soldier. I'm not at this point really dying to give a long gory account of all the cute neuroses that more or less around that time began to pop up all over the inside of my brain, sort of like wrinkly gray boils, but I'll tell a few things. For one thing, I was throwing up a lot, feeling really nauseated all the time, especially when I'd wake up in the morning. But it could switch on anytime, the second I began to think about it: If I felt OK, all of a sudden I'd think, "Hey, I don't feel nauseated at all, here." And it would just switch on, like I had a big white plastic switch somewhere along the tube from my brain to my hot and weak stomach and intestines, and I would just throw up all over my plate at dinner or my desk at school or the seat of the car, or my bed, or wherever. It was really highly grotesque for everyone else, and intensely unpleasant for me, as anyone who has ever felt really sick to his stomach can appreciate. This went on for quite a while, and I lost a lot of weight, which was bad because I was quite thin and non-strong to begin with. Also, I had to have a lot of medical tests on my stomach, involving delicious barium drinks and being hung upside down for X-rays, and so on, and once I even had to have a spinal tap, which hurt more than anything has ever hurt me in my life, I am never ever going to have another spinal tap.

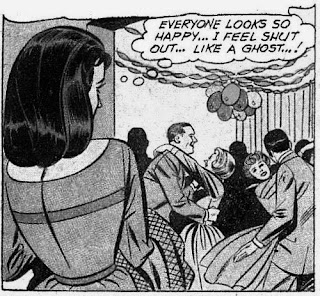

Also, there was this business of crying for no reason, which wasn't painful but was very embarrassing and also quite scary because I couldn't control it. What would happen is that I'd cry for no reason, and then I'd get sort of scared that I'd cry or that once I started to cry I wouldn't be able to stop, and this state of being scared would very kindly activate this other white switch on the tube between my brain with its boils and my hot eyes, and off I'd go even worse, like a skateboard that you keep pushing along. It was very embarrassing at school, and incredibly embarrassing with my family, because they would think it was their fault, that they had done something bad. It would have been incredibly embarrassing with my friends, too, but by that time I really didn't have very many friends. So that was kind of an advantage, almost. But there was still everyone else. I had little tricks I employed with regard to the "crying problem." When I was around other people and my eyes got all hot and full of burning saltwater I would pretend to sneeze, or even more often to yawn, because both these things can explain someone's having tears in his eyes. People at school must have thought I was just about the sleepiest person in the world. But, really, yawning doesn't exactly explain the fact that tears are just running down your cheeks and raining down on your lap or your desk or making little wet star puckers on your exam papers and stuff, and not too many people get super red eyes just from yawning. So the tricks probably weren't too effective. It's weird but even now, here on the planet Trillaphon, when I think about it at all, I can hear the snap of the switch and my eyes more or less start to fill up, and my throat aches. That is bad. There was also the fact that back then I got so I couldn't stand silence, really couldn't stand it at all. This was because when there was no noise from outside the little hairs on my eardrums or wherever would manufacture a noise all by themselves, to keep in practice or something. This noise was sort of a high, glittery, metallic, spangly hum that really for some reason scared the living daylights out of me and just about drove me crazy when I heard it, the way a mosquito in your ear in bed at night in summer will just about drive you crazy when you hear it. I began to look for noise sort of the way a moth looks for light. I'd sleep with the radio on in my room, watch an incredible amount of loud television, keep my trusty Sony Walkman on at all times at school and walking around and on my bike (that Sony Walkman was far and away the best Christmas present I have ever received). I would even maybe sometimes talk to myself when I had just no other recourse to noise, which must have seemed very crazy to people who heard me, and I suppose was very crazy, but not in the way they supposed. It wasn't as if I thought I was two people who could have a dialogue, or as if I heard voices from Venus or anything. I knew I was just one person, but this one person, here, was a troubled little soldier who could withstand neither the substance nor the implications of the noise produced by the inside of his own head.

Anyway, all this extremely delightful stuff was going on while I was doing well and making my otherwise quite wor· ried and less than pleased patents happy school-wise during the year, and then while I was working for Exeter Building and Grounds Department during the following summer, pruning bushes and crying and throwing up discreetly into them, and while I was packing and having billions of dollars of clothes and electrical appliances bought for me by my grandparents, gelling all ready to go to Brown University in Rhode Island in September. Mr. Film, who was more or less my boss at "B and G," had a riddle that he thought was unbelievably funny and he told it to me a lot. He'd say, "What's the color of a bowel movement?" And when I didn't say anything he'd say. "Brown! har har har!" He'd laugh and I'd smile, even after about the four-trillionth time, because Mr. Film was on the whole a fairly nice man, and he didn't even get mad when I threw up in his truck once. I told him my scar was from getting cut up with a knife in high school, which was essentially the truth.

So I went off to Brown University in the fall, and it turned out to be very much like "P .G." at Exeter: it was supposed to be all hard but it really wasn't, so I had plenty of time to do well in classes and have people say "Outstanding" and still be neurotic and weird as hell, so that my roommate, who was a very nice, squeakingly healthy guy from Illinois, understandably asked for a single instead and moved out in a few weeks and left me with a very big single all my very own. So it was just little old me and about nine billion dollars worth of electronic noise-making equipment, there in my room, after that. It was quite soon after my roommate moved out that the Bad Thing started. The Bad Thing is more or less the reason why I'm not on Earth anymore. Dr. Kablumbus told me after I told him as best I could about the Bad Thing that the Bad Thing was "severe clinical depression." I am sure that a doctor at Brown would have told me pretty much the same thing, but I didn't ever go to see anyone at Brown, mainly because I was afraid that if I ever opened my mouth in that context stuff would come out that would ensure that I'd be put in a place like the place I was put after the hilariously stupid business in the bathroom.

I really don't know if the Bad Thing is really depression. I had previously sort of always thought that depression was just sort of really intense sadness, like what you feel when your very good dog dies, or when Bambi's mother gets killed in Bambi. I thought that it was that you frowned or maybe even cried a little bit if you were a girl and said "Holy cow,l'm really depressed, here," and then your friends if you have any come and cheer you up or take you out and get you ploughed and in the morning it's like a faded color and in a couple days it's gone altogether. The Bad Thing - which I guess is what is really depression - is very different, and indescribably worse. I guess I should say rather sort of indescribably, because I've heard different people try to describe "real" depression over the last couple years. A very glib guy on the television said some people liken it to being underwater, under a body of water that has no surface, at least for you, so that no matter what direction you go, there will only be more water, no fresh air and freedom of movement, just restriction and suffocation, and no light. (I don't know how apt it is to say it's like being underwater, but maybe imagine the moment in which you realize, at which it hits you that there is no surface for you, that you're just going to drown in there no matter which way you swim; imagine how you'd feel at that exact moment, like Descartes at the start of his second thing, then imagine that feeling in all its really delightful choking intensity spread out over hours, days, months ... that would maybe be more apt.) A really lovely poet named Sylvia Plath, who unfortunately isn't living anymore, said that it's like having a jar covering you and having all the air pumped out of the jar, so you can't breathe any good air (and imagine the moment when your movement is invisibly stopped by the glass and you realize you're underglass ...). Some people say it's like having always before you and under you a huge black hole without a bottom, a black, black hole, maybe with vague teeth in it, and then your being part of the hole, so that you fall even when you stay where you are (. . . maybe when you realize you're the hole, nothing else .. .)

I'm not incredibly glib, but I'll tell what I think the Bad Thing is like. To me it's like being completely, totally, utterly sick. I will try to explain what I mean. Imagine feeling really sick to your stomach. Almost everyone has felt really sick to his or her stomach, so everyone knows what it's like: it's less than fun. OK. OK. But that feeling is localized: it's more or less just your stomach. Imagine your whole body being sick like that: your feet, the big muscles in your legs, your collarbone, your head, your hair, everything, all just as sick as a fluey stomach. Then, if you can imagine that, please imagine it even more spread out and total. Imagine that every cell in your body, every single cell in your body is as sick as that nauseated stomach. Not just your own cells, even, but the e-coli and lactobacilli in you, too, the mitochondria, basal bodies, all sick and boiling and hot like maggots in your neck, your brain, all over, everywhere, in everything. All just sick as hell. Now imagine that every single atom in every single cell in your body is sick like that, sick, intolerably sick. And every proton and neutron in every atom. . . swollen and throbbing, off-color, sick, with just no chance of throwing up to relieve the feeling. Every electron is sick, here, twirling off balance and all erratic in these funhouse orbitals that are just thick and swirling with mottled yellow and purple poison gases, everything off balance and woozy, Quarks and neu- trinos out of their minds and bouncing sick all over the place, bouncing like crazy. Just imagine that, a sickness spread utterly through every bit of you, even the bits of the bits. So that your very . . . very essence is characterized by nothing other than the feature of sickness; you and the sickness are, as they say, "one." That's kind of what the Bad Thing is like at its roots. Everything in you is sick and grotesque. And since your only acquaintance with the whole world is through parts of you - like your sense-organs and your mind, etc. - and since these parts are sick as hell, the whole world as you perceive it and know it and are in it comes at you through this filter of bad sickness and becomes bad. As everything becomes bad in you, all the good goes out of the world like air out of a big broken balloon. There's nothing in this world you know but horrible rotten smells, sad and grotesque and lurid pastel sights, raucous or deadly sad sounds. Intolerable open-ended situations lined on a continuum with just no end at all. .. Incredibly stupid, hopeless ideas. And just the way when you're sick to your stomach you're kind of scared way down deep that it might maybe never go away, the Bad Thing scares you the same way, only worse, because the fear is itself filtered through the bad disease and becomes bigger and worse and hungrier than it started out. It tears you open and gcts in there and squirms around. Because the Bad Thing not only attacks you and makes you feel bad and puts you out of commission, it especially attacks and makes you feel bad and puts out of commission precisely those things that are necessary in order for you to fight the Bad Thing, to maybe get better, to stay alive. This is hard to understand, but it's really true. Imagine a really painful disease that, say, attacked your legs and your throat and resulted in a really bad pain and paralysis and all around agony in these areas. The disease would be bad enough, obviously, but the disease would also be open-ended; you wouldn't be able to do anything about it. Your legs would be all paralyzed and would hurt like hell ... but you wouldn't be able to run for help for those poor legs, just exactly because your legs would be too sick for you to run anywhere at all. Your throat would burn like crazy and you'd think it was just going to explode ... but you wouldn't be able to call out to any doctors or anyone for help, precisely because your throat would be too sick for you to do so. This is the way the Bad Thing works: it's especially good at attacking your defense mechanisms. The way to fight against or get away from the Bad Thing is clearly just to think differently, to reason and argue with yourself, just to change the way you're perceiving and sensing and processing stuff. But you need your mind to do this, your brain cells with their atoms and your mental powers and all that, your self, and that's exactly what the Bad Thing has made too sick to work right. That's exactly what it has made sick. It's made you sick in just such a way that you can't get better. And you start thinking about this pretty vicious situation, and you say to yourself, "Boy oh boy, how the heck is the Bad Thing able to do this? You think about it - really hard, since it's in your best interests to do so - and then all of a sudden it sort of dawns on you ... that the Bad Thing is able to do this to you because you're the Bad Thing yourself! The Bad Thing is you. Nothing else: no bacteriological infection or having gotten conked on the head with a board or a mallet when you were a little kid, or any other excuse; you are the sickness yourself. It is what "defines" you, especially after a little while has gone by. You realize all this, here. And that, I guess, is when if you're all glib you realize that there is no surface to the water, or when you bonk your nose on the jar's glass and realize you're trapped, or when you look at the black hole and it's wearing your face. That's when the Bad Thing just absolutely eats you up, or rather when you just eat yourself up. When you kill yourself. All this business about people committing suicide when they're "severely depressed;" we say, "Holy cow, we must do something to stop them from killing themselves!" That's wrong. Because all these people have, you see, by this time already killed themselves, where it really counts. By the time these people swallow entire medicine cabinets or take naps in the garage or whatever, they've already been killing themselves for ever so long. When they "commit suicide," they're just being orderly. They're just giving external form to an event the substance of which already exists and has existed in them over time. Once you realize what's going on, the event of self-destruction for all practical purposes exists. There's not much a person is apt to do in this situation, except "formalize" it, or, if you don't quite want to do that, maybe "E.C.T." or a trip away from the Earth to some other planet, or something.

Anyway, this is more than I intended to say about the Bad Thing. Even now, thinking about it a little bit and being introspective and all that, I can feel it reaching out for me, trying to mess with my electrons. But I'm not on Earth anymore.

I made it through my first little semester at Brown University and even got a prize for being a very good introductory Economics student, two hundred dollars, which I promptly spent on marijuana, because smoking marijuana keeps you from getting sick to your stomach and throwing up. It really does: they give it to people undergoing chemotherapy for cancer, sometimes. I had smoked a lot of marijuana ever since my year of "P.G." schoolwork to keep from throwing up, and it worked a lot of the time. It just bounced right off the sickness in my atoms, though. The Bad Thing just laughed at it. I was a very troubled little soldier by the end of the semester. I longed for the golden good old days when my face just bled.

In December the Bad Thing and I boarded a bus to go from Rhode Island to New Hampshire for the holiday season. Everything was extremely jolly. Except just coming out of Providence, Rhode Island, the bus driver didn't look carefully enough before he tried to make a left turn and a pickup truck hit our bus from the left side and smunched the left front part of the bus and knocked the driver out of his seat and down into the well where the stairs onto and off of the bus are, where he broke his arm and I think his leg and cut his head fairly badly. So we had to stop and wait for an ambulance for the driver and a new bus for us. The driver was incredibly upset. He was sure he was going to lose his job, because he'd messed up the left turn and had had an accident, and also because he hadn't been wearing his seat belt - clear evidence of which was the fact that he had been knocked way out of his seat into the stairwell, which everybody saw and would say they saw - which is against the law if you're a bus driver in just about any state of the Union. He was almost crying, and me too, because he said he had about seventy kids and he really needed that job, and now he would be fired. A couple of passengers tried to soothe him and calm him down, but understandably no one came near me. Just me and the Bad Thing, there. Finally the bus driver just kind of passed out from his broken bones and that cut, and an ambulance came and they put him under a rust-colored blanket. A new bus came out of the sunset and a bus executive or something came too, and he was really mad when some of the incredibly helpful passengers told him what had happened. I knew that the bus driver was probably going to lose his job, just as he had feared would happen. I felt unbelievably sorry for him, and of course the Bad Thing very kindly filtered this sadness for me and made it a lot worse. It was weird and irrational but all of a sudden I felt really strongly as though the bus driver were really me. I really felt that way. So I felt just like he must have felt, and it was awful. I wasn't just sorry for him, I was sorry as him, or something like that. All courtesy of the Bad Thing. Suddenly I had to go somewhere, really fast, so I went to where the driver's stretcher was in the open ambulance and went in to look at him, there. He had a bus company ID badge with his picture, but I couldn't really see anything because it was covered by a streak of blood from his head. I took my roughly a hundred dollars and a bag of "sinsemilla" marijuana and slipped it under his rusty blanket to help him feed all his kids and not get sick and throw up, then I left really fast again and got my stuff and got on the new bus. It wasn't until, what, about thirty minutes later on the nighttime highway that I realized that when they found that marijuana with the driver they'd think it was maybe his all along and he really would get fired, or maybe even sent to jail. It was kind of like I'd framed him, killed him, except he was also me, I thought, so it was really confusing. It was like I'd symbolically killed myself or something, because I felt he was me in some deep sense. I think at that moment I felt worse than I'd ever felt before, except for that spinal tap, and that was totally different. Dr. Kablumbus says that's when the Bad Thing really got me by the balls. Those were really his words. I'm really sorry for what I did and what the Bad Thing did to the bus driver. I really sincerely only meant to help him, as if he were me. But I sort of killed him, instead.

I got home and my parents said "Hey, hello, we love you, congratulations:' and I said "Hello, hello, thank you, thank you,"I didn't exactly have the "holiday spirit," I must confess, because of the Bad Thing, and because of the bus driver, and because of the fact that we were all three of us the same thing in the respects that mattered at all.

The highly ridiculous thing happened on Christmas Eve. It was very stupid, but I guess almost sort of inevitable given what had gone on up to then. You could just say that I'd already more or less killed myself internally during the fall semester, and symbolically with respect to that bus driver, and now like a tidy little soldier I had to "formalize" the whole thing, make it neat and right-angled and external; I had to fold down the corners and make hospital corners. While Mom and Dad and my sisters and Nanny and Pop-Pop and Uncle Michael and Aunt Sally were downstairs drinking cocktails and listening to a beautiful and deadly-sad record about a crippled boy and the three kings on Christmas night, I got undressed and got into a tub full of warm water and pulled about three thousand electrical appliances into that tub after me. However, the consummate silliness of the whole incident was made complete by the fact that most of the appliances were cleverly left unplugged by me in my irrational state. Only a couple were actually "live," but they were enough to blowout the power In the house and make a big noise and give me a nice little shock indeed, so that I had to be taken to the hospital for physical care. I don't know if I should say this, but what got shocked really the worst were my reproductive organs. I guess they were sort of out of the water part-way and formed a sort of bridge for the electricity between the water and my body and the air. Anyway, their getting shocked hurt a lot and also I am told had consequences that will become more significant if I ever want to have a family or anything. I am not overly concerned about this. My family was concerned about the whole incident, though; they were less than pleased. to say the least. I had sort of half passed out or gone to sleep, but I remember hearing the water sort of fizzing, and their coming in and saying "Oh my God, hey!" I remember they had a hard time because it was just pitch-black in that bathroom, and they more or less only had me to see by. They had to be extremely careful getting me out of the tub, because they didn't want to get shocked themselves. I find this perfectly understandable.

Once a couple days went by in the hospital and it became clear that boy and reproductive organs were pretty much going to survive, I made my little vertical move up to the White Floor. About the White Floor - the Troubled Little Soldier Floor - I really don't wish to go into a gigantic amount of detail. But I will tell some things. The White Floor was white, obviously, but it wasn't a bright, hurty white, like the burn ward. It was more of a soft, almost grayish white, very bland and soothing. Now that I come to think back on it, just about everything about the White Floor was soft and unimposing and ... demure, as if they tried really hard there not to make any big or strong impressions on any of their guests - sense-wise or mind-wise - because they knew that just about any real impression on the people who needed to go to the White Floor was probably going to be a bad impression. after being filtered through the Bad Thing.

The White Floor had soft white walls and soft light-brown carpeting, and the windows were sort of frosty and very thick. All the sharp corners on things like dressers and bedside tables and doors had been beveled-off and sanded round and smooth, so it all looked a little strange. I have never heard of anyone trying to kill himself on the sharp corner of a door, but I suppose it is wise to be prepared for all possibilities. With this in mind, I'm sure, they made certain that everything they gave you to eat was something you could eat without a knife or a fork. Pudding was a very big item on the White Floor. I had to wear a bit of a thing while I was a guest there, but I certainly wasn't strapped down in my bed, which some of my colleagues were. The thing I had to wear wasn't a straitjacket or anything, but it was certainly tighter than your average bathrobe, and I got the feeling they could make it even tighter if they felt it was in my best interests to do so. When someone wanted to smoke a tobacco cigarette, a psychiatric nurse had to light it, because no guest on the White Floor was allowed to have matches. I also remember that the White Floor smelled a lot nicer than the rest of the hospital, all feminine and kind of dreamy, like ether.

Dr. Kablumbus wanted to know what was up, and I more or less told him in about six minutes. I was a little too tired and torn up for the Bad Thing to be super bad right then, but I was pretty glib. I rather liked Dr. Kablumbus, although he sucked on very nasty-smelling candies all the time - to help him stop smoking, apparently - and he was a bit irritating in that he tried to talk like a kid - using a lot of curse words, etc. - when it was just quite dear that he wasn't a kid. He was very understanding, though, and it was awfully nice to see a doctor who didn't want to do stun to my reproductive organs all the time. After he knew the general scoop, Dr. Kablumbus laid out the options to me, and then to my parents and me. After we all decided not to therapeutically convulse me with electricity, Dr. Kablumbus got ready to let me leave the Earth via antidepressants.

Before I say anything else about Dr. Kablumbus or my little trip, I want to tell very briefly about my meeting a colleague of mine on the White Floor who is unfortunately not living anymore, but not through any fault of her own whatsoever, rather through the fault of her boyfriend. who killed her in a car crash by driving drunk. My meeting and making the acquaintance of this girl, whose name is May, even now stands out in my memory as more or less the last good thing that happened to me on Earth. I happened to meet May one day in the TV room because of the fact that her turtleneck shirt was on inside out. I remember The Uttle Rascals was on and I saw the back of a blond head belonging to who knows what sex, there, because the hair was really short and ragged, And below that head there was the size and fabric-composition tag and the white stitching that indicates the fact that one's turtleneck shirt is on inside out. So I said, "Excuse me, did you know your shirt was on inside out?" And the person, who was May, turned around and said, "Yes I know that:" When she turned I could not help noticing that she was unfortunately very pretty, I hadn't seen that this was a pretty girl, here, or else I almost certainly wouldn't have said anything whatsoever. I have always tried to avoid talking to pretty girls, because pretty girls have a vicious effect on me in which every part of my brain is shut down except for the part that says unbelievably stupid things and the part that is aware that I am saying unbelievably stupid things. But at this point I was still too tired and torn up to care much, and I was just getting ready to leave Earth, so I just said what I thought, even though May was disturbingly pretty. I said, "Why do you have it on inside out?" referring to the shirl. And May said, "Because the tag scratches my neck and I don't like that." Understandably, I said, "Well, hey, why don't you just cut the tag out?" To which I remember May replied, "Because then I couldn't tell the front of the shirt:" "What?"I said, wittily. May said, "It doesn't have any pockets or writing on it or anything. The front is just exactly like the back. Except the back has the tag on it. So I wouldn't be able to tel1." So I said, "Well, hey, if the front's just like the back, what difference does it make which way you wear it?" At which point May looked at me all seriously, for about eleven years, and then said. "It makes a difference to me." Then she broke into a big deadly, pretty smile and asked me tactfully where I got my scar. I told her I had had this annoying tag sticking out of my cheek ...

So, just more or less by accident, May and I became friends, and we talked some. She wanted to write made-up stories for a living. I said I didn't know that could be done. She was killed by her boyfriend in his drunken car only ten days ago. I tried to call May's parents just to say that I was incredibly sorry yesterday, but their answering service informed me that Mr. and Mrs. Aculpa had gone out of town for an indefinite period. I can sympathize, because I am "out of town," too.

Dr. Kablumbus knew a lot about psychopharmaceuticals. He told my parents and me that there were two general kinds of antidepressants: tricyclic5 and M.A.O. inhibitors (I can't remember what "M.A.O." stands for exactly, but I have my own thoughts with respect to the matter). Apparently both kinds worked well, but Mr. Kablumbus said that there were certain things you couldn't eat and drink with M.A.O. inhibitors, like beer, and certain kinds of sausage. My Mom was afraid I would forget and maybe eat and drink some of these things, so we all conferred and decided to go with a tricyclic. Dr. Kablumbus thought this was a very good choice.

Just as with a long trip you don't reach your destination right away, 50 with antidepressants you have to "go up" on them: i.e,. you start with a very tiny little dose and work your way up to a full-size dose in order to get your blood level accustomed and all that. So, in one way, my trip to the planet Trillaphon took over a week. But in another way, it was like being off Earth and on the planet Trillaphon right from the very first morning after I started. The big difference between the Earth and the planet Trillaphon, of course, is distance: the planet Trillaphon is very very far away. But there are other differences that are sort of more immediate and intrinsic. I think the air on the planet Trillaphon must not be as rich in oxygen or nutrition or something because you get a lot tireder a lot faster there. Just shoveling snow off a sidewalk or running to catch a bus or shooting a couple baskets or walking up a hill to sled down gets you very, very tired. Another annoying thing is that the planet Trillaphon is tilted ever so slightly on its axis or something, so that the ground when you look at it isn't quite level; it lists a little to starboard. You get used to this fairly quickly, though, like getting your "sea legs" when you're on a ship.

Another thing is that the planet Trillaphon is a very sleepy planet. You have to take your antidepressants at night, and you better make sure there is a bed nearby, because it will be bedtime incredibly soon after you take them. Even during the day, the resident of the planet Trillaphon is a sleepy little soldier. Sleepy and tired, but too far away to be super-troubled.

This has nothing to do with the very ridiculous incident in the bathtub on Christmas Eve, but there is something electrical about the planet Trillaphon. On Trillaphon for me there isn't the old problem of my head making silence into a spangly glitter, because my tricyclic antidepressant - "Tofranil" - makes a sort of electrical noise of its own that drowns the spangle out completely. The new noise isn't incredibly pleasant, but it's better than the old noises, which I really couldn't stand at all. The new noise on my planet is kind of a high-tension electric trill. That's why for almost a year now I've somehow always gotten the name of my antidepressant wrong when I'm not looking right at the bottle: I've called it 'Trillaphon" instead of "Tofranil," because "Trillaphon" is more trilly and electrical, and it just sounds more like what it's like to be there. But the electricalness of the planet Trillaphon is not just a noise. I guess if I were all glib like May is I'd say that "the planet Trlllaphon is simply characterized by a more electrical way of life:" It is, sort of. Sometimes on the planet Trillaphon the hairs on your arms will stand up and a chill will go through the big muscles in your legs and your teeth will vibrate when you close your mouth, as if you're under a high-tension line, or by a transformer. Sometimes you'll crackle for no reason and see blue things. And even the sound of your brain-voice when you think thoughts to yourself on the planet Trillaphon is different than it was on Earth; now it sounds like it's coming from a sort of speaker connected to you only by miles and miles and miles of wire, like you're back listening to the "Golden Days of Radio.'

It is very hard to read on the planet Trillaphon, but that is not too inconvenient, because I hardly ever read anymore, except for "Newsweek" magazine, a subscription which I got for my birthday, I am twenty-one years old.

May was seventeen years old. Now sometimes I'll sort of joke with myself and say that I need to switch to an M.A.O. inhibitor. May's initials are M.A., and when I think about her now I get so sad I go "0." In a way, I would understandably like to inhibit the "M.A.O." I'm sure Dr. Kablumbus would agree that it is in my own best interests to do so. If the bus driver I more or less killed had the initials M.A., that would be incredibly ironic.

Communications between Earth and the planet Trillaphon are hard, but they are very inexpensive, so I am definitely probably going to call the Aculpas to say just how sorry I am about their daughter, and maybe even that I more or less loved her.

The big question is whether the Bad Thing is on the planet Trillaphon. I don't know if it is or not. Maybe it has a harder time in a thinner and less nutritious atmosphere. I certainly do, in some respects. Sometimes, when I don't think about it, I think I have just totally escaped the Bad Thing, and that I am going to be able to lead a Normal and Productive Life as a lawyer or something here on the planet Trillaphon, once I get so I can read again.

Being far away sort of helps with respect to the Bad Thing.

Except that is just highly silly when you think about what I said before concerning the fact that the Bad Thing is really me.

2.THE DEPRESSED PERSON